The Abbotsford Lumber Company’s employment of Chinese, Japanese, and Sikh workers allowed for these communities to establish bonds to Canada and made Abbotsford a multicultural city from its pioneer days. Although there were many positive connections made from these cross-cultural interactions, there were also very apparent racial tensions in Abbotsford in the 1920s. The mill, despite allowing different ethnic communities the chance to form constructive relationships, also served to incite racial hostilities in the white settler community.

SUSPICIOUS ACTIVITY

By the 1920s, the Abbotsford Lumber Company’s diverse workforce was well established, though during this decade, resistance to Asian and South Asian workers increased. Although some of this aversion to immigrant workers was openly discussed and acted upon, there were some suspicious events which could be related to racial hostility. The most significant of these is a fire which took place in June of 1924. The alarm was raised at 2:30 A.M. on a Sunday morning at the Abbotsford Lumber Company. The flames appeared to have started in a newly built Japanese boarding house, which quickly spread to the South Asian bunkhouse, as well as burned down three Japanese cottages.1 Those on site managed to put out the flames before the whole property was engulfed, but the damage still amounted to four or five thousand dollars. It has to be acknowledged that in a time period with limited electricity, fires were significantly more common, and this event at the mill could be no different; however, no cause of the fire was ever determined, and the only buildings lost were those inhabited by the Asian employees of the mill. This fire may not have been arson, but it was certainly a suspicious event at the mill site.

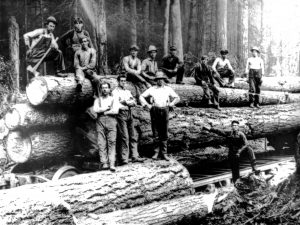

Loggers on tracks used by the Abbotsford Lumber Company in 1925. Photo courtesy of The Reach Gallery Museum. P6002.

Beyond the suspect activity in Abbotsford, the city also was home to some who were overtly opposed to the Asian and South Asian workers at the Abbotsford Lumber Company. One such opposition group was the Native Sons of Canada, who believed that British protestants were the “native sons” of the nation, and thus opposed those of other ethnicities and religions. At the 26th Sumas Prairie Assembly meeting of this organisation on the 16th of December 1927, a resolution was passed which directly asked the Abbotsford Lumber Company to remove all their “oriental” employees, another common term for Asian and South Asian immigrants at the time. This resolution, first moved by A. Campbell, and seconded by S.A. Cawley, outlined the groups’ feelings towards the Asian employees. They were concerned about the “Oriental” engaging in employment “competition with the White Race.”2 They wanted unemployed white men to take the positions of the Asian employees at the mill and stated that this replacement would increase business for local merchants and improve lands. They claimed that the Asian employees were of less benefit to Abbotsford than a true British citizen would be, and resolved to ask the Abbotsford Board of Trade Committee to join with the Native Sons in confronting the Abbotsford Lumber Company with the request of firing their Asian and South Asian labour force. It was an astonishing request, though it did receive support from members of the community. In March of 1928, the Abbotsford Sumas and Matsqui News published an article supporting the Native Sons’ efforts. They promoted an earlier campaign by the nativist group which had its members sending pieces of British Columbia lumber to federal Members of Parliament, with the following message attached:

BRITSH COLUMBIA’S FORESTS – A SOUVENIR with the compliments of Sumas Prairie Assembly, No. 26 NATIVE SONS OF CANADA, Abbotsford, B.C. I AM A NATIVE of British Columbia, produced to this stage by 65% ORIENTAL LABOR. WE HAVE, in our Province, 46,000 Orientals who are unfairly competing with white labor. The Dominion collects the Head-tax, while the Province of British Columbia carries the burden. Having paid this tax, these Orientals are entitled to reside SOMEWHERE in Canada. Should the Oriental Labour Problem become unbearable to British Columbians and should they in their extremity decide to secede from the Dominion to deal with this problem – To What Other Part of Canada Will These Orientals Be Acceptable?”3

Not only do the Native Sons’ actions demonstrate blatant aversion to having Chinese, Japanese, and Sikh employees at the mill, but the support they received from the community further demonstrates that the mill’s hiring of Asian employees was contentious. Although there were positive interactions which stemmed from this relationship, there were certainly negative ones as well.

Abbotsford at this time was also home to another infamous white supremacist group: the Klu Klux Klan. This organization has become known in public awareness for their hostile and racist actions in America, but they also appeared in Canada, though in a slightly different form. The K.K.K. in Abbotsford tended to focus on passionate opposition to the Roman Catholic church. In March of 1928, the Abbotsford Sumas and Matsqui News began reporting on a series of events hosted by the K.K.K. First, there were lectures delivered by a Reverend J. Murray Hanna supporting anti-Roman Catholicism. The newspaper listed some of his former lectures, one of which was titled, “Is the white race slipping?”4 demonstrating some level of racial tension within the Abbotsford members of the Klu Klux Klan. Following the lectures, the Abbotsford Sumas and Matsqui News reported on an “Impressive Display” held in Abbotsford: a parade.5 Attended by K.K.K. members from Bellingham, Vancouver, and New Westminster, the parade on Essendene was fronted by a drum and fife band, and a flaming crucifix was carried throughout. The parade was attended by hundreds of Abbotsford residents, indicating some level of popularity.

At least one Abbotsford resident didn’t agree with the Klan’s display. The following week in the paper’s letters to the editor, an H.T. Peters wrote the following, “It does no good to stir up strife in this manner, let us adhere to the principle of freedom in religious beliefs, and cultivate the spirit of tolerance.”6 Interestingly, in response to this criticism of the Klan, a letter was issued in retaliation written by a Mr. Howard Trethewey, giving his support to the lectures by Reverend Hanna, and the Klu Klux Klan actions, stating that “the dangers which confront the Protestant citizens in Canada to-day were exposed by the lecturer.”7 Although the actions of the Klu Klux Klan in Canada concentrated primarily on the issue of threats to the Protestant faith, the Asian and South Asian employees of the mill, as members of differing religious faiths, represented one such threat to these nativist groups. The Abbotsford Lumber Company’s employment of diverse peoples was therefore a contentious and complex issue.

NEXT PAGE → THE MILL REACTS

NOTES

1. “Five Buildings at Mill Destroyed by Flames,” Abbotsford Sumas Matsqui News, June 19, 1924. The Reach Gallery Museum.

2. Resolution of the Native Sons of Canada Sumas Prairie Assembly, No. 26, 1924. The Reach Gallery Museum. Folder: Abbotsford Lumber Company.

3. “Must B.C. Secede To Effect Oriental Ban Sumas Native Sons’ Assembly Asks Ottawa,” Abbotsford Sumas and Matsqui News, March 7, 1928. The Reach Gallery Museum.

4. “Klu Klux Klansmen Holding Meetings,” Abbotsford Sumas and Matsqui News, March 7, 1928. The Reach Gallery Museum.

5. “Klansmen Give Impressive Display in Abbotsford,” Abbotsford Sumas and Matsqui News, March 7, 1928. The Reach Gallery Museum.

6. Peters, H.T. “Did Not Approve Klan Display,” Abbotsford Sumas and Matsqui News, March 14, 1928. The Reach Gallery Museum.

7. Trethewey, Howard. “Taken Issue with Mr. Peters,” Abbotsford Sumas and Matsqui News, March 21, 1928. The Reach Gallery Museum.